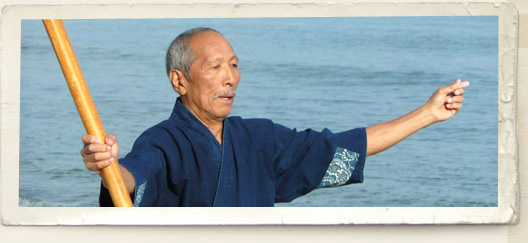

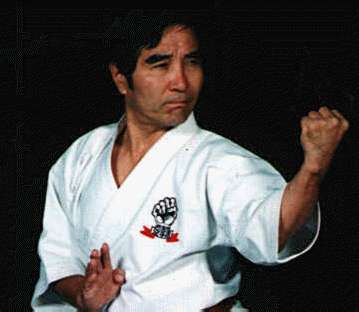

The reminiscences of Kimiyoshi Suzuki sensei

I was born in January 1, 1934 in Tokyo, as the second

child of a middle-class family. The tradition of martial arts come from

my grandfather on my mother's side, Shigekatsu Makita, a last descendant

of a samurai family, who lived in Aizu originally, and moved to Hokkaido

after the fall of the Tokugawa dinasty.

Jikishin Kage-ryu Kenjutsu became famous in Japan in the 18th century,

thanks to Kenkichi Sakakibara (1829-1894), a high ranked samurai. His

best disciple, and the future heir of the school was Yasutoshi* Matsudaira

(1835-????). My grandfather used to train in Yasutoshi's dojo. His talent

and lineage would have ensured him the title of the grandmaster after

the death of Yasutoshi, as the 16th successor. But history altered his

path. The new laws of Emperor Meiji in 1867 revoked the privileges of

the samurai, and made the succession impossible. During these days, it

was very hard to find a job, and make a living for warriors like him.

His kind suddenly became obsolete. Thanks to the name of his school, and

his reputation as a swordsman, he was offered a job as a police officer.

He accepted, and moved to the village of Atsuta. In the beginning of the

1900s he opened his dojo called "Jikishin Kan", and continued teaching

kenjutsu, kyudo, and kendo. He died in 1914. His followers raised a memorial

for him, that can be seen in the center of the village even today. Later,

a book was published of his life, that shows a true picture of the life

of the last representatives of samurai.

My father was a photographer. He left Japan at the age of 20, and went

to New York. He returned Tokyo for his mother's sake in 1932. He never

did any martial arts, but had a valuable collection of fifty pieces of

katana and wakizashi. Unfortunately during and after the second world

war, we had to move often, and the American troops were confiscating swords

as dangerous weapons. Almost all the collection was lost. I only could

save a single wakizashi.

My father took me to learn kendo when I was six years old. The dojo was

in a garden of a nearby shinto temple, where Yokokawa sensei was teaching

us. Simultaneously, I started to train with a judo master called Suzuki

sensei with a few friends of mine. In the postwar times, all forms of

budo was forbidden by the American forces, training was possible only

secretly, in small rooms among the closest friends. This period lasted

for eight years, masters could reopen their schools in 1953. I used the

chance instantly, and went to the central dojo of the famous Goju-ryu

master, Gogen Yamaguchi (1909-1989), and applied to be his trainee. In

the same year I got into the Tokyo University of Arts, to the faculty

of photographing.

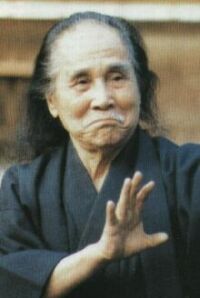

Yamaguchi

sensei was a kind, humble, and modest person, he never drank alcohol,

never smoked, and lived a very religious life. I had two hour trainings

every afternoon, in the three storeyed central building of the dojo. As

far as I can remember, sometimes three or four hundred people were training

simultaneously in bigger and smaller groups. During the practises, Gogen

was sitting in the corner of the room, and was watching our moves carefully.

Sometimes he stood up, and corrected someones mistakes. The exams were

completely differend than todays'. The senior students proposed the people

in their groups, they thought to be ready for being examinated by the

master. I was nominated for 1st kyu exam by a 3rd dan senior in 1954.

I can say I had no free time at all. I was studiyng in the university

in the morning, and I was training in the dojo every afternoon. I used

my weekends to work in the photo studio.

Yamaguchi

sensei was a kind, humble, and modest person, he never drank alcohol,

never smoked, and lived a very religious life. I had two hour trainings

every afternoon, in the three storeyed central building of the dojo. As

far as I can remember, sometimes three or four hundred people were training

simultaneously in bigger and smaller groups. During the practises, Gogen

was sitting in the corner of the room, and was watching our moves carefully.

Sometimes he stood up, and corrected someones mistakes. The exams were

completely differend than todays'. The senior students proposed the people

in their groups, they thought to be ready for being examinated by the

master. I was nominated for 1st kyu exam by a 3rd dan senior in 1954.

I can say I had no free time at all. I was studiyng in the university

in the morning, and I was training in the dojo every afternoon. I used

my weekends to work in the photo studio.

I completed the 1st dan's exam in 1955. In the trainings of Yamaguchi

sensei, the fights werevery important, and we always had to do them with

full power, but control. The karate wasn't a sport back then. On Gogen's

trainings there were a lot of kumite, even with other groups of sudents.

Sometimes against them, we could even lose control... Once a tall and

strong looking young man came to our group. We fought many times later. He

was the founder of Kyokushinkai karate, Oyama Masutatsu (1923 - 1994).

When Mas opened his first dojo in Tokyo, he asked me, and other higher

ranked seniors, to help him to make the first steps. We had a good relationship.

He

was the founder of Kyokushinkai karate, Oyama Masutatsu (1923 - 1994).

When Mas opened his first dojo in Tokyo, he asked me, and other higher

ranked seniors, to help him to make the first steps. We had a good relationship.

I finished university in 1957, and became photo-reporter and journalist

of a daily newspaper in Tokyo. Of course, I never stopped doing karate.

Gogen Yamaguchi asked me to teach in Honbu in 1959, that's when I met

his son, Goshi (1942-) who was a very good friend of mine. He later became

the grandmaster of his fathers' school.

My father decided to retire in 1960 and left his photo shop and studio

for me. I kept on working there for more than thirty years, until my own

retirement. By Goju-ryu, I started to learn aikido in 1960 from Hiroshi

Tada sensei (1929-). When I recall those years, I see that my whole life

was about working and training. I spent all my free time in dojos. Days,

weeks and even years were washed away in a blink of an eye. I walked a

very hard path, till I took my 6th dan grade from the hands of Gogen Yamaguchi.

In these times kenjutsu wasn't too popular in Japan. Young people rather

chose kendo instead of kenjutsu, because it was much more sportlike, modern.

If memory serves me good, maybe Katori Shinto ryu Kenjutsu was the most

widespread. the old masters died out slowly. There's hardly any people

left who teaches the traditional styles, the ancient forms of gendai budo

are slowly sinking into oblivion.

I first met Hungarian artists in 1986, who were visitors in Japan. I came

to Hungary the first time on their invitation. First to Budapest, then

to Pécs. That's where I met my wife, Kati as well, and that's where

we settled down together.

Goshi

Yamaguchi shihan asked me to meet Rebicek Gerd in 1991. He was the senior

instructor of Goju-ryu Karate in Hungary. There was a Japanese cultural

event in Pécs in 1992, where I invited three of my friends from

Japan, and we held a demonstration. That's how it spread that I know martial

arts. One day a few neighbourhood boys came to me, and asked mo to teach

them. We didn't even have a proper place to train, we kept our sessions

in my living room. Later, I went to the University of Sciences in Pécs

in 1993, and rent the gym, where I started my "Shinbukan" dojo.

I keep karate and kenjutsu trainings there today.

Goshi

Yamaguchi shihan asked me to meet Rebicek Gerd in 1991. He was the senior

instructor of Goju-ryu Karate in Hungary. There was a Japanese cultural

event in Pécs in 1992, where I invited three of my friends from

Japan, and we held a demonstration. That's how it spread that I know martial

arts. One day a few neighbourhood boys came to me, and asked mo to teach

them. We didn't even have a proper place to train, we kept our sessions

in my living room. Later, I went to the University of Sciences in Pécs

in 1993, and rent the gym, where I started my "Shinbukan" dojo.

I keep karate and kenjutsu trainings there today.

Jikishin Kage-ryu Kenjutsu - as I mentioned before - Is a very rare, and

forgotten school in Japan. When I traveled home once, I tried to find

a dojo where I used to train, but I couldn't find it. I learned that the

master was long dead. When someone asked me to start kenjutsu trainings,

for a few enthusiastic locals, I never even dreamed how popular it will

be. If my grandfather could see how we are rebuilding this old style with

the Hungarians, he would be very happy.

The bokken is very important in Jikishin Kage-ryu. We practise cuts to

all parts of the body, like the head, body, arms and legs. We don't use

any kind of protecting suit, so timing and control is essential. We have

another bokken-like weapon, a heavy, thick, and straight log, in the same

length as a katana. We use this for building up strenght, and performing

traditional kata (like Hojo). We use katana (Iaito) for Iai practise,

and cutting sword for tameshigiri and demonstration. There wasn't anything

like exams or ranks in the early Japan like today. When the master found

his apprentice ready, he orderd him to show his knowledge. There were

three levels in Jikishin Kage-ryu. The reiken, the normal trainee level,

the moku-reiken, the advanced level, and the highest menkyo kaiden, was

the masters' level, and gave the owner the right to start teaching. The

diplomas were hand-written, and contained every technique the examinee

showed before the master. If the exam was successful, the new master could

wear the hakama. This represented todays black belt. These thigs have

changed nowadays, we use the same kyu-dan method as in most of the martial

arts.

The motto of our Jikishin Kage-ryu Kenjutsu dojo is: "Be your sword

sharp, and fast as lightning, but keep your soul in calmness". In

Japanese: "Ken wa surudoku, ki wa maruku". I suggest this to

everyone, who does some sort of martial art.

I hope the trainees understand, that the teachings of the old days can

show solutions to the problems of the present. All should show respect

to the ancestors and each other who seek the answers on the ways of martial

arts. May them be Hungarians or Japanese.

(This article was published in two parts under the title

of "The living history" in Katana Magazin 2003, 2004

interview by László Kehidai)

* = In the original article it went by the name "Konen" but the correct reading is "Yasutoshi".